When a beam supports a slab (or when it carries another beam only on its one side), it is subjected to direct torsion.

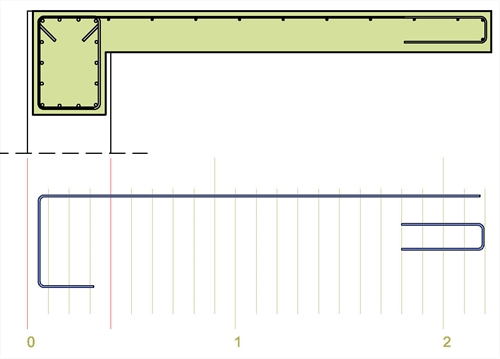

Beam under direct torsion "project: beams40"

Beam under direct torsion "project: beams40" Beam under direct torsion "project: beams40"

For common buildings in areas with high seismic activity, torsion is a quite dangerous stress condition, because:

a) It is a statically determined stress. This means that if a failure occurs there is no possibility for transition to another static state.

b) The rotations caused to the beam due to creep are relatively large thus leading to large slab deformations.

c) Failure is caused by shear stresses therefore, it is of brittle nature and consequently there are no signs of the impending failure.

d) It is not easy for the technicians to understand that the formwork of the elements under torsion must not be removed the usual time. On the contrary, the formwork must remain in place until the following-phase-casted-concrete that affects these elements is adequately hardened.

e) Reinforcing beams subjected to torsion follows special rules. In order to apply these rules, one does not only require thorough knowledge but also extreme care during the implementation.

Whether the beam section is hollow or solid it counteracts with the torsional moment and maintains a state of equilibrium with a closed flow of torsional shear stresses, in a peripheral zone.

Due to the high shear strength requirements, beams under torsion, are usually constructed with a large width. That way the beam’s section approximates the square shape.

Torsion causes diagonal tensile stresses along the entire perimeter of the beam and in order for these stresses to be carried both longitudinal and vertical reinforcement is required. The longitudinal reinforcement at the upper and lower side of the beam is provided by the upper and lower rebars, while the longitudinal reinforcement of the side-faces is provided by the rebars placed along the stirrups’ legs length.

The longitudinal rebars of the support areas are required to withstand the highest torsional stresses. Therefore, in order to behave in the required way, all rebars placed at the upper, lower and side parts of the beam must be properly anchored inside the column.

In order for the vertical reinforcement i.e. the stirrups to carry the required stresses; they must be properly closed therefore, it is mandatory to be formed with a double hook.

In order to be able to place the slab reinforcement, the beam’s formwork must have its back side-face open.

In order to be able to place the slab reinforcement, the beam’s formwork must have its back side-face open. In order to be able to place the slab reinforcement, the beam’s formwork must have its back side-face open.

The rebars of the slab supported by a beam, must be anchored at least with double bending, as shown at the above detail. The rest of the reinforcement has to abide by the rules regarding cantilevers as explained in the following chapter.

In order to be able to place the slab’s rebars, the formwork must have its back side-face open. Alternatively, the vertical slab bar could be constructed 50 mm shorter so as to be placed unobstructed above the longitudinal reinforcement at the bottom part of the beam.

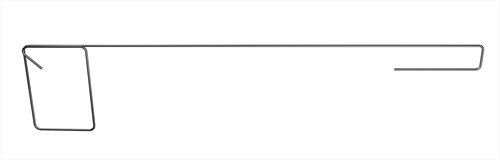

There is also another more complex but old and well-tried practice: in the slab area where torsion appears, the stirrup and the slab rebar are formed with one single bar, as shown at the figure bellow.

The reinforcement solution with unified stirrups – rebars in the slab area

The reinforcement solution with unified stirrups – rebars in the slab area The reinforcement solution with unified stirrups – rebars in the slab area